Despite criticism that the billions invested in the CCT program could have been better spent on job creation and that many poor families were missed, the government argues that it has not only improved school attendance and health care coverage, but has actually reduced violence in conflict-ridden areas.

Today, the government intends to spend even more on its flagship poverty alleviation program, as it hopes to target greater student attendance in high school and not just in elementary. By 2015, a quarter of the population is expected to be beneficiaries, including new categories for coverage such as abandoned children, the disabled, and those displaced by calamities or conflict. No social protection program in Philippine history has ever reached this breathtaking breadth and scale.

Lila Ramos Shahani of the Aquino administration’s Human Development and Poverty Reduction Cabinet Cluster explains.

No other anti-poverty program has ever attracted the kind of sustained global attention that Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) have. Funded by the World Bank and other international institutions, they began as far back as the 1990s in Brazil and other parts of Latin America. Since then, CCT programs in a variety of permutations have spread swiftly across many parts of the globe. They have not only been applied in developing countries but even metropolitan cities like New York, where poverty continues to remain a glaring problem.

Why this avid receptivity to CCTs the world over? Simply defined, CCTs make a set amount of cash available to families for the education and health of their children. Receipt of these funds is contingent upon meeting the criteria of the government and fulfilling their obligations. Unlike Keynesian-inspired welfare programs of the past, which had aimed to provide benefits for all citizens, CCTs take on a more neo-liberal approach to the provision of basic social services.

They target only those who are considered to be the poorest of the poor. The receipt of cash is based upon the behavior of recipients. In effect, CCTs are designed to discipline parents in assuming direct responsibility for the welfare of their children. The State acts simply to monitor (and, if necessary, mediate in order to protect) the welfare of the child, rather than to intervene directly. More importantly, CCTs are meant to effect generational change: they are not meant to produce immediate effects in the here and now (a minor detail nay-sayers conveniently tend to ignore) but are designed to address poverty across future generations.

As with any new and rapidly-spreading program, CCTs have had mixed results, calling for refinements and re-calibrations from place to place. In this article, we will review the state of CCTs in the Philippines — currently, the most ambitious and far-reaching anti-poverty measure of this or any other administration. We will examine its applications, its successes, and its possible shortcomings. Finally, we will look at current recommendations by different scholars and policy experts for improving the program.

The 4Ps

Some four million of the country’s poorest households are now receiving conditional transfers under the government’s flagship anti-poverty program, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, or 4Ps.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), in its first quarterly report of the year, reported that the 4Ps have reached 100% coverage in the regional, provincial, and municipal levels, and a 98.54% coverage rate at the barangay level.

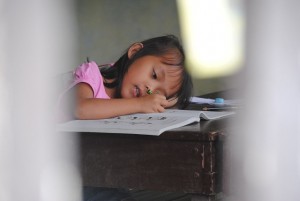

The program hopes to invest in the country’s human capital by keeping poor children in school and giving them medical assistance, while extending immediate financial support to their families. The cash transfers are dependent upon each household’s compliance with these conditions. As of the first quarter of this year, compliance rates for both the education and health components have been high — an impressive 96% school attendance rate and 95% immunization rate for beneficiary children, not to mention a significant improvement in the delivery of health services for women and their children.

Considering that maternal mortality happens to be one of the biggest social challenges today (with a high 221 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births, making this our poorest national achievement in terms of the Millennium Development Goals), the fact that CCTs have encouraged women to seek health care before and after child birth has been critical.

Social Welfare Secretary Dinky Soliman recently observed that women in 4P families tend to have at least four prenatal checkups, improving compliance to a high 64 percent, in comparison to the low 54 percent for non-4P beneficiaries. An impact evaluation of the 4Ps done last year by the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and Australian Aid further emphasized that mothers in 4P families generally received more health care before and after child birth compared to those not enrolled in the program.

Aside from targeting children, the program also aspires to help parents. The program provides for Family Development Sessions (FDS) meant to empower parents and better equip them to look after their children.

Early success

Historically, the 4Ps have been the country’s biggest social protection program, emulating the successful conditional cash transfer programs in Latin America, particularly Brazil’s Bolsa Familia and Mexico’s Oportunidades.

Bolsa Familia is considered one of the most active contributors to Brazil’s social and economic transformation. First implemented in 2003, it is now the world’s largest CCT program, reaching more than 46 million people.

Since 2011, Brazil has lifted around 22 million Brazilians out of extreme poverty. It is reported that the share of wealth of Brazil’s richest 20% declined over the past decade, while the poorest 20% increased their share from 2.6 to 3.5%.

The equally-lauded Oportunidades of Mexico, meanwhile, has been credited with lowering the incidence of illness among children enrolled in the program.

Reducing conflict

After just five years, the 4Ps have also been shown to impact not just individual families but entire communities.

In a recent University of Denver study entitled “Conditional Cash Transfers and Civil Conflict: Experimental Evidence from the Philippines” by Crost, Felter and Johnston, the 4Ps were cited as a primary factor in reducing the incidence of conflict in the country.

The study, which primarily used data from the Armed Forces of the Philippines, demonstrates that there was a sharper decrease in the number of reported conflicts in villages where the program was introduced in 2009 than in those where the program was delayed until 2010.

The Philippines is home to some of the world’s longest-running communist and Islamic insurgencies.

The study demonstrates that cash transfers encourage the public to trust the government and provide them with valuable information regarding insurgents. More importantly, cash transfers increase the opportunity cost of joining an insurgency, since it becomes difficult for anyone to receive payments once they become an active insurgent.

Direct cash transfers like the 4Ps are also seen as being more effective in reducing conflict than community-driven development (CDD) programs or food aid, which attract attention, are easily intercepted, and are more likely to be sabotaged by insurgent groups. Physical and in-kind aid also increases the amount of resources conflicting parties could fight over.

A study done on Colombia’s version of CCTs, Familias en Acción, by the German Economic Association further reveals that CCTs help increase enrolment in conflict-stricken areas. Like the Philippines, Colombia suffers from a long-running separatist guerrilla movement.

Leakage rate

The program has been praised by international organizations like the World Bank (WB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for its significant role in the improvement of health and education among the poor.

Not everyone is impressed, however, with some claiming that that the 4Ps are nothing but a band-aid masquerading as a form of genuine social protection.

IBON Foundation, a non-stock and non-profit development organization, sees them as a dole-out program that merely exacerbates the country’s debt — after all, the program is partially funded through loans from the WB and ADB.

IBON claims that the 4Ps are unsustainable and that their impact upon poverty alleviation has been insignificant.

KADAMAY (Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap), an urban poor organization, also claims that, despite the enormous budget allotted for CCTs, the program has not truly improved the lives of the poor.

In a public debate held by KADAMAY in February of this year, their leader, Carlito Badion, argued that the government, instead of allocating millions for CCTs, should instead spend its budget on strengthening industries that could generate jobs for the poor.

Indeed, it must be admitted that, despite the country’s outstanding GDP growth of 7.8% this quarter, the Philippines has been unsuccessful in reducing the income gap. The latest National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) report shows that the country’s poverty incidence has remained virtually unchanged since 2006.

The Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), the country’s leading policy think tank, reveals in a study that the 4Ps have been missing some of their targeted families. The study, conducted by Dr. Celia Reyes of PIDS and presented at the recently concluded Global Development Conference at the Asian Development Bank, suggests that the 4Ps have a leakage rate of around 29%.

This means that only 70.81% of the total number of beneficiaries are actually income poor and belong to the bottom fifth of the population.

And, of those who are income poor, only 7.2% became non-poor when given cash transfers.

DSWD identifies beneficiary families through a combination of geographic targeting and a Proxy-Means-Testing (PMT) method, known as the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction (NHTS-PR). Municipalities are selected if they have a poverty incidence rate of 50% or higher. Using the NHTS-PR, households are categorized as poor if their predicted incomes fall below the provincial poverty threshold. If a family has a pregnant woman or children between 0-14 at the time of the assessment, they are enrolled in the program.

The NHTS-PR has identified a total of 5.2 million poor families in the country, eighty-two percent of whom live in rural areas.

High school completion

Reyes also notes that school enrolment in 4P families falls significantly for children aged 13 and above. This means that, as children from beneficiary families become ineligible for cash transfers, there is less incentive for them to continue schooling.

As such, according to PIDS, school attendance among 4P families falls drastically as a child grows older: from 93.6% for those aged 13 to just 33.8% for those aged 18.

There appears to be no significant difference in school attendance for those aged 15-18 between 4P families and non-4P families.

In an earlier policy paper, Reyes compared the Philippines’ version of the CCTs to those of its Latin American counterparts — Mexico’s Oportunidades extends cash assistance up to the age of 22 or until a student graduates from high school, with more money given to those in the higher grades. Economic incentives are also given to those who graduate from high school before the age of 22.

Brazil’s Bolsa Familia, likewise, gives greater subsidies to adolescents than to children, and covers them until they are 17 years old.

Reyes points out that the program should aim for high school rather than elementary completion, as there is higher pay and more employment opportunities for high school graduates than elementary graduates.

PIDS notes that, in the Philippines, those who have earned a high school diploma earn at least 45% higher than those who have only attended some years of elementary. This suggests one way in which the 4Ps could theoretically strengthen their investment in human capital.

Boys left behind

Sadly, many boys from the poorest families are leaving the school system early to help augment their family incomes.

In the same Global Development conference, it was generally agreed that income disparity was one of the most significant impediments to solving global poverty. In a seminal study by Hugo Ñopo and Alejandro Hoyos on the Latin American experience, it was established that over a decade of investment in CCTs has had a significant impact on income inequality in the aggregate. However, it was also found that poverty in the long run had not always been reduced, in large part because of a worsening in the standard of education, among other worrisome factors.

In a nutshell: boys from the lowest 20th percentile of the population are leaving schools to look for work, or worse: to join gangs and go into drugs. As one WB policy wonk put it: however politically incorrect it might be, it is now high time we started to focus on our lost boys.

Indeed, the report reveals that, in 2011, more boys (22%) than girls (8.3%) tended to drop out of school at the age of 15 throughout the region. Six out of ten 18-year old boys were working instead of studying.

In this country, we will have to brace ourselves for the possibility that this may well happen in the near future: hence the need to fine-tune existing programs. NSCB Secretary-General Jose “Toots” Gatmaitan Albert advocates having distinct levels of support for children of different ages, rather than a blanket P300 per month for each child. Ideally, boys, like older children, should be given higher support (as with Mexico’s Oportunidades). More importantly, support has to extend so children can finish high school.

Future plans: Modified CCTs

PIDS suggests that the program should focus on providing longer assistance — from five to 10 years, or even longer — to current beneficiaries to ensure that their children finish high school.

To address the issue, Budget Secretary Florencio Abad says that government officials are now considering the idea of extending the CCT program to ensure that its beneficiaries will finish high school, which would then give them greater employment opportunities.

The government has made plans not only to increase the number of beneficiaries, but also to extend coverage in general.

A “modified” conditional cash transfer or MCCT approach is now in the works to include families who have been displaced by calamities and conflict, who belong to Indigenous Peoples’ groups, and who have children in need of special assistance.

Such children are those who may have various forms of disability, who have been abandoned, or who have been forced to engage in child labor.

To solve the leakage rate, the National Household Targeting Office (NHTO) at DSWD now conducts a validation activity, where the community verifies the list of poor households in their respective areas. The list is posted in conspicuous places throughout the community, which encourages the public to react if and when they disagree with any particular family listed.

Complaints and queries are then received by NHTO staff members, who forward it to a Local Verification Committee which, in turn, resolves these complaints and appeals.

As the country races to meet the Millennium Development Goals, the government gears up its efforts to bring development to all sectors of society. Longer-term returns on investment in human capital, after all, will not be seen overnight, and it is well worth to remember that CCTs are ultimately a social investment for the future.

The NSCB estimates that around P180 billion is needed yearly for the government’s poverty alleviation program, and the CCT’s P39-billion allotment last year has only increased to P44 billion this year.

Budgetary constraints notwithstanding, the 4Ps has managed to make enormous headway in improving school enrolment, immunization, and even resolving conflict in targeted families and communities.

In 2015, the 4Ps are projected to cover some 28 million poor Filipinos — a quarter of the nation’s population. No social protection program in our history has ever reached this breathtaking breadth and scale. But even as our economy grows in leaps and bounds, we must continue to make every effort to ensure that no Filipino — no matter how poor — is ever left behind.

Lila Ramos Shahani is Head of Communications of the Human Development and Poverty Reduction Cabinet Cluster, which includes 26 government agencies dealing with poverty and development. She would like to thank Ralph Angelo Ty and Fritzie Rodriguez for their help with this piece.